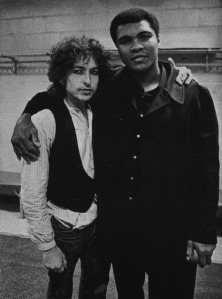

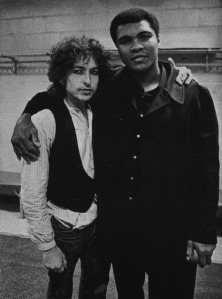

“If the measure of greatness is to gladden the heart of every human being on the face of the earth, then he truly was the greatest. In every way he was the bravest, the kindest and the most excellent of men.”

Bob Dylan

As so often happens when I want to say something profound, the old Bard beats me to it. (It would surprise some to know that Dylan is a trained fighter who even ran a private boxing gym behind his Santa Monica coffee house for several years).

As so often happens when I want to say something profound, the old Bard beats me to it. (It would surprise some to know that Dylan is a trained fighter who even ran a private boxing gym behind his Santa Monica coffee house for several years).

What can be said about Muhammad Ali that hasn’t already been said in the past week? I can only offer a personal perspective. Like Jackie Robinson, Ali was at the confluence of sports, race, politics, and a changing culture. But unlike Jackie, his triumphs and struggles were contemporaneous with my own life. It might be difficult for those who didn’t live through it to comprehend that the man who later became beloved as a world icon was reviled, rejected, and even hated by many. First, he refused to become the establishment’s version of what a black athlete should be: polite, grateful, deferential. Even before his name change he was a controversial figure: brash, boastful, supremely confident – almost no one gave him a chance of defeating Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion. And once he did, he almost immediately changed his name, his religion, and fell in with Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, and the Nation of Islam. This was a time when Martin Luther King was still considered “controversial” for using non-violent methods to try to get the vote for his people, so figures like Malcolm and the Black Muslims were beyond exotic. They were considered real threats to the social order. Ali’s principled stand against serving in the Vietnam War not only brought him the acrimony of the white power structure, but also criticism from respected black figures like Jackie Robinson himself. Not only was he stripped of his title at the prime of his athletic life, but his passport was taken, and he could not earn a living anywhere in the world. But when he said his reasons for not going to Vietnam included the fact that no Vietnamese person had ever called him the N-word or raped his mother, it was pretty hard to argue with him. His willingness to give up everything and even go to jail for his principles gradually brought him respect even from those who disagreed with him. (The Supreme Court, of course, eventually overturned his conviction by unanimous vote).

Ali was not a saint. His mocking of Joe Frazier, a proud black athlete in his own right, and a man who quietly supported him and lent him money when Ali could not fight professionally, was a disgrace, and the lingering bitterness lasted until Frazier’s death. For a time Ali spouted a lot of separatist Nation Of Islam dogma about the evils of the white man, and the desirability of the separation of the races. He even turned his back on his great friend Malcolm X after Malcolm fell afoul of Elijah Muhammad and his cronies, something Ali always regretted. But gradually Ali’s faith took on a more universalist tone, and he embraced the world. His heart and his mind proved simply too big for narrow ideologies.

As a boxer, Ali was unorthodox. He was not the hardest-hitting heavyweight, nor the biggest, but he used leg motion (his famous “dancing”) to mesmerize his opponents, and more often than not they found themselves on the receiving end of lethal combinations coming from his lightning-fast hands. He fought backing up with his hands lowered – two boxing no-no’s, but this style was extremely effective for him. His bluster and clowning were, I believe, partly a tactic to hide the fact that he was a master tactician. The Foreman fight in which he introduced the “rope-a-dope” was pure genius. He let the younger, bigger man punch himself out and frustrate himself until Ali seized his moment in Round Eight and Foreman fell like a lumbering tree. In short, Ali was beautiful to watch. Even if you weren’t a boxing fan, you could be an Ali fan. When I took up boxing at the ripe old age of 49 I tried to emulate Ali’s style, never mind that I didn’t have the quickness, stamina, or chin. But I still practice that fast left jab followed by that sharp downward right hand.

I met him once, at an industry show. It was years after his retirement and his Parkinson’s disease had already taken hold. I thought about how cruel it was for a man with such gifts to be ridden with such a horrible disease. The hands that were once so quick now shook, and the mouth that once spewed poetry and wit like a verbal machine gun could not form more than the simplest words.

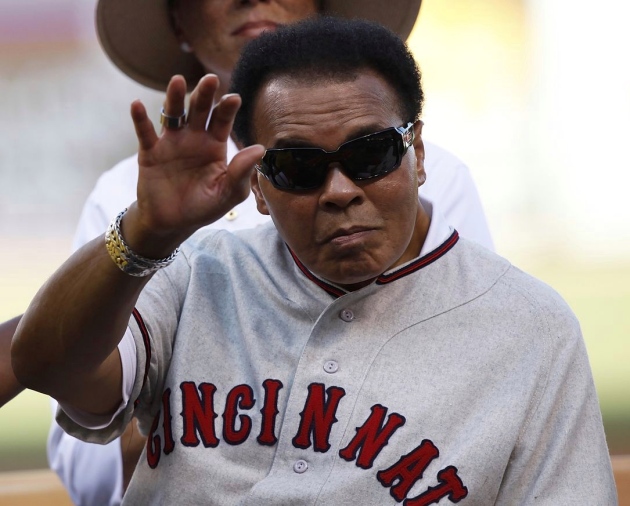

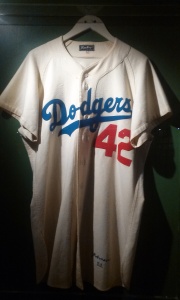

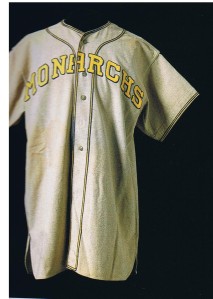

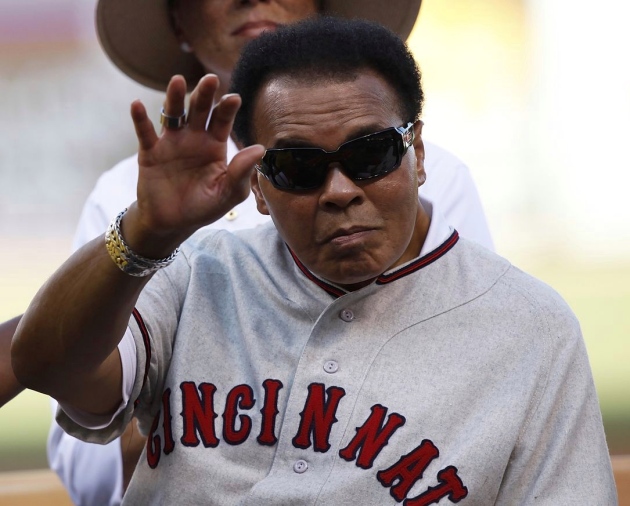

Several years ago, I was thrilled when we were asked to make a jersey for Muhammad for the Civil Rights Game, that year played in Cincinnati. It remains one of my proudest moments.

The sport of boxing – which once rivaled baseball for popularity – is a shadow of its former self, particularly the heavyweight division, which was once populated by names like Louis, Marciano, Patterson, Liston, Frazier, Foreman, and Ali. We are lucky that every once in a while, people walk among us who do more than entertain us – they change us.

As so often happens when I want to say something profound, the old Bard beats me to it. (It would surprise some to know that Dylan is a trained fighter who even ran a private boxing gym behind his Santa Monica coffee house for several years).

As so often happens when I want to say something profound, the old Bard beats me to it. (It would surprise some to know that Dylan is a trained fighter who even ran a private boxing gym behind his Santa Monica coffee house for several years).