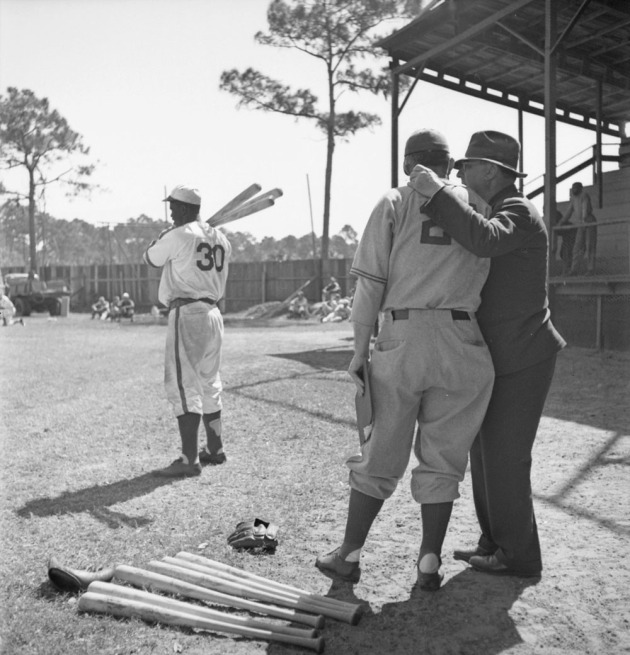

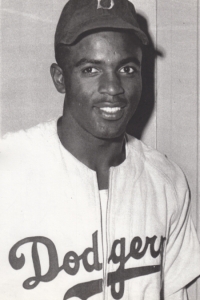

Robinson’s first Dodger home uniform.

In the two previous posts we discussed the uniforms worn by Jackie Robinson in his Negro league and minor league careers. From 1947 until his final season of 1956, his uniforms are of course synonymous with the uniforms of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Although the primary elements of the Dodger uniforms (particularly at home) have remained almost unchanged from Robinson’s first season up through today, there were several minor changes between 1947 and 1956. First, it must be said that I think it’s sad that Robinson never actually wore a uniform with “Brooklyn” on it. The last flannel road uniforms to say “Brooklyn” were worn in 1945, with the city name not being returned to the road shirts until 1958, when the Bums were on the opposite coast. Jackie started out his rookie season in a zipper-front raglan sleeved jersey with the familiar “Dodgers” in royal blue script emblazoned across the front. There was no trim on the jersey, and the script font was slightly more angular than the later version. Note that the lettering splits between the “d” and “g”. The split between “o” and “d” began in 1950, and has remained in force through today.

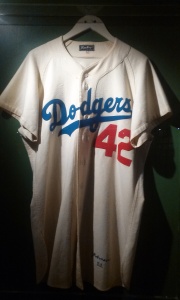

Jackie Robinson’s 1950 Home Jersey

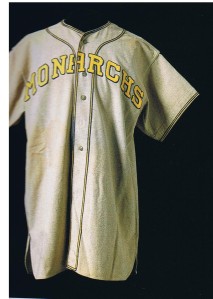

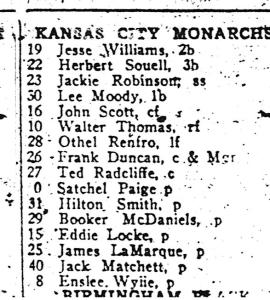

The road jerseys were button-front with narrow blue trim (called “soutache” in our trade). In 1950 the letters moved to their familiar position on the jersey, and in 1951 a patch commemorating the 50th anniversary of the National League was added to the left sleeve (as it was on all NL clubs). The final big change to the Dodger uniforms was in 1952, when a large red number was added to the front of the jersey, below the lettering. It is interesting that the Dodgers chose a red number, because no red had been a Dodgers uniform since 1936. There are several theories about the origin of the red numbers, and most people assign credit to principal owner Walter O’Malley for the innovation. It is likely that the numbers were added with television in mind, a new phenomenon is sports which would have wide implications in uniform design. One story suggests that O’Malley added the numbers for the 1951 World Series, a series that of course the Dodgers would never play in due to unexpected events at the Polo Grounds that October. Whatever the reason, the red numbers were here to stay, though they wouldn’t be added to the road uniforms until the club moved to Los Angeles in 1958.

Red numbers were added in 1952. Home jersey only.

Last Brooklyn road jersey, note trim.

Let’s talk jackets. The Dodgers wore a plethora of jackets in different fabrics during the Robinson era. There were all-wool styles, wool with leather sleeves, and fur-lined “Skinner satin” jackets (a high quality rayon satin fabric), similar to the one we made for the Bert Shotten character in the film “42”.

1955 Skinner Satin jacket

All-wool jacket made by Butwin of Minnesota.

Leather sleeve jacket with matching gold trim.